“The level of the most important heat-trapping gas in the atmosphere, carbon dioxide, has passed a long-feared milestone, reaching a concentration not seen on the earth for millions of years,” the New York Times reported today.

“It symbolizes that so far we have failed miserably in tackling this problem,” said Pieter P. Tans, who runs the monitoring program at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “It takes a long time to melt ice, but we’re doing it,” another climate scientist said. “It’s scary.”

“It symbolizes that so far we have failed miserably in tackling this problem,” said Pieter P. Tans, who runs the monitoring program at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “It takes a long time to melt ice, but we’re doing it,” another climate scientist said. “It’s scary.”

“For the entire period of human civilization, roughly 8,000 years,” the article goes on, “the carbon dioxide level was relatively stable. But the burning of fossil fuels has caused a 41 percent increase in the heat-trapping gas since the Industrial Revolution, a mere geological instant, and scientists say the climate is beginning to react.”

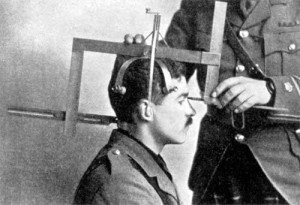

Aristotle laid out the grid for the Western mind. And with the ending of a distinctly different Eastern mind in the last few decades, the Western mind has become, for better but mostly worse, the world mind. Aristotle made modern science possible, but he was mistaken to give knowledge the highest priority.

Modern science and technology are the zenith of Aristotle’s framework and the Western mind. But a pervasive and globalizing meaninglessness and emptiness, not to mention the rapacious destruction of nature, are its nadir. Though they may not know it, at bottom Islamic extremists are raging against the Western mind, not the Judeo-Christian world.

The crisis of consciousness facing humankind is total and unprecedented. Not only are beliefs, traditions and institutions incapable of meeting it, it goes beyond these expressions of different cultures to the foundation in thought and knowledge of consciousness.

The task before philosophy is nothing less than to radically change the globalized Western mindset without diminishing the scientific enterprise, and bring about a new mind. That begins within the individual, through right observation of the movement of thought/emotion, which opens space for insight in the mind of the undivided human being.

With the explosion of scientific knowledge, it has become abundantly clear that knowledge does not bring about wisdom. Furthermore, scientific knowledge does not speak to humankind’s capacity for wonder and urge for union with nature  and the immanent; indeed it is diminishing and denying them.

and the immanent; indeed it is diminishing and denying them.

There are of course rational and irrational forms of knowledge. But the crisis of consciousness goes beyond the usual distinction between scientific and other types of knowledge, since insight, understanding and wisdom are not a function of knowledge of any kind.

The idea that scientific knowledge, or any other kind of knowledge, can answer all questions and solve all problems is hubris of the highest order.

Pursuing scientific knowledge for its own sake, or for the betterment of humanity, is a good thing. Making knowledge the highest good however, means plunging ahead in the wrong direction, the direction that Aristotle largely set.

Rational and testable explanations of the workings and origin of the universe are desirable, if never completely attainable, goals. But such explanations have to include humankind–our contradiction with nature and fragmentation of the earth. Man is a sentient species knowingly destroying climatic balance and producing the mass extinction of other species.

Therefore, while we should always seek rational explanations, we can never be satisfied with them, or confuse them with  understanding. Knowledge can never be complete, and the wonder, mystery, and reverence for life flow from a completely different source.

understanding. Knowledge can never be complete, and the wonder, mystery, and reverence for life flow from a completely different source.

It’s an unseasonably warm spring afternoon, even in northern California. A quarter mile from the parking lot, I pass a young couple sitting in large lawn chairs, complete with beer in drink holders, iPads and other paraphernalia.

About a dozen vultures are circling lazily in a gentle breeze over the gorge and canyon in the relatively unspoiled Upper Park. They are graceful searchers for gruesome remains. Without the associations that go with the name and knowledge of vultures, they are seen as they are.

Sitting on the ground at the lip of the gorge for over an hour, I don’t see another soul. The vertical slabs are stained with ochre, and subtle shades of yellow and red run down many of their faces. As the mind completely quiets and meditation deepens, the sight of the angular, colored rocks evokes not merely centuries, but millennia, including the long and tortuous history of man.

A few vultures glide down the gorge below eye level, only a few meters away. I can see their vigilant eyes in their red heads, and the long feathers protruding from the ends of their wings look like delicate fingers.

To keep growing as a human being, one has to learn the art of attention, which allows the brain to be deeply and effortlessly quiet. When the mind can totally set aside the movement of thought, memory and knowledge, and be fully aware and awake, it is alight with insight.

Such a human being is realizing a cosmic intent, an intent that is without a deity, plan, or design. This intent is intrinsic to evolution, inherent in the development of galaxies, stars, planets, and life forms everywhere in the universe.

Martin LeFevre